智慧商(shang)業解決方案(an)

Solution

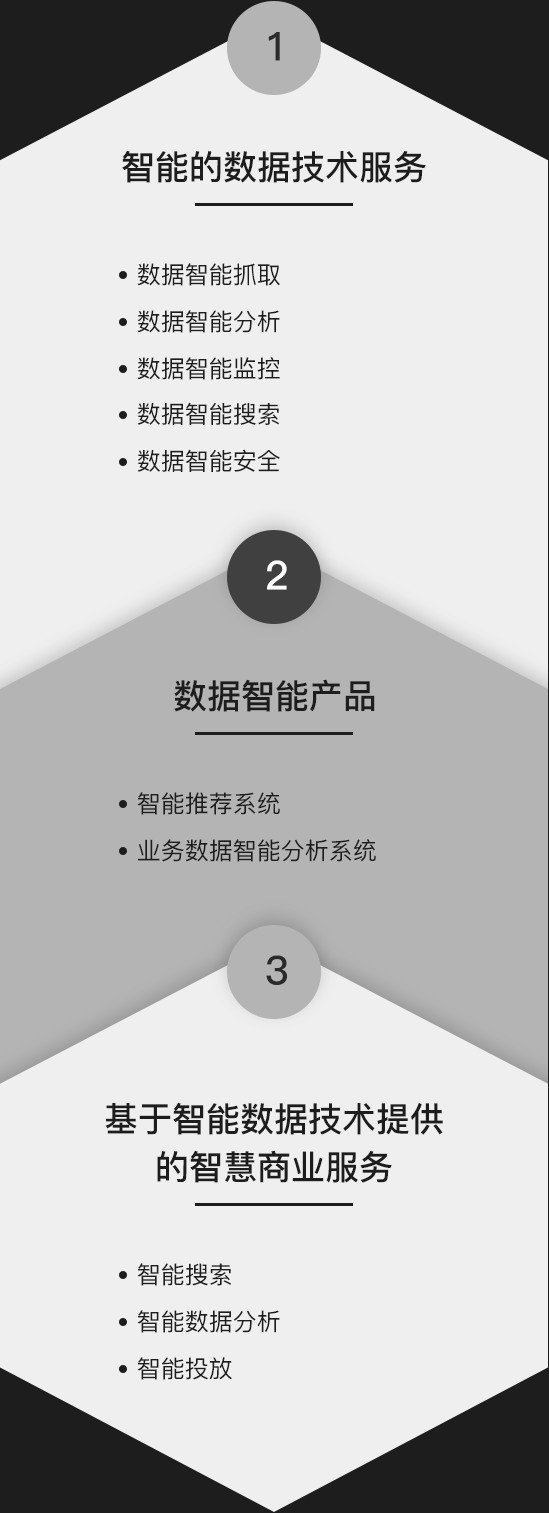

能力表述(shu)

Ability Expression

用戶案例

Customer Case

跨(kua)境電商

海外產(產)品發行

銀行業(業)

保(bao)險業

| 体内精69XXXXXx精油,久久日产一线二线三线,国产日产欧美产,国品一二三产区区别麻豆,欧洲尺码日本尺码专线 | 国产成人午夜精华液,国产suv精品一区二区6精华液,av一区二区精华液,国产精华液久久久,国产精品2024 | 性少妇videosexfreexxxx片,两根大肉大捧一进一出好爽视频,一级毛片久久久久久久女人18免费观看在线下载播放 |